The month of March is Women’s History Month, but like so many women-led companies, we honor women’s accomplishments all year long. One of the most memorable ways we’ve done this is the collection we released in 2018, which drew inspiration from traditional women-made textiles around the globe. Women’s Work is a tribute to the artistry, ingenuity, and creativity of women, spanning six continents and several centuries of history. (It also happens to be one of my personal favorites.)

The month of March is Women’s History Month, but like so many women-led companies, we honor women’s accomplishments all year long. One of the most memorable ways we’ve done this is the collection we released in 2018, which drew inspiration from traditional women-made textiles around the globe. Women’s Work is a tribute to the artistry, ingenuity, and creativity of women, spanning six continents and several centuries of history. (It also happens to be one of my personal favorites.)

Our intention is to honor the women (and, yes, a few good men) who created these traditions, techniques, and processes. It goes so much deeper than dipping into history for references: for us, it’s about preserving these crucial voices, allowing their unique perspectives to live on as textile tradition evolves, and celebrating their devotion to the craft.

So, in the spirit of honoring women’s history — all year long, I might add — let’s revisit Women’s Work, and take a closer look at some of the individual pieces that inspired it. We’ll start with some of the pieces from Africa.

The reference from the earliest known knit textile is our Coptic Sock. The oldest knit artifacts are from Egypt in the 4th to 5th century. Although fragments of the textiles remain, the needles used in the making have not, and careful examination indicates this may have been made with a single needle. The process would be closer to sewing a series of loops together, rather than the knitting process of today. The socks were constructed of white and indigo cotton.

Akan Kente Cloth is from Ghana. Traditional kente are made of woven silk and cotton. For the Akan, it is still considered a sacred, royal cloth, and worn for important occasions. Both pattern and color are significant to the wearer, and colors have symbolic meanings.

Ibo Akwete Cloth originated in Nigeria. It is a woven construction of sisal, hemp, raffia and spun cotton. The warps were solid or multi-colored, single or double face weaving constructions. Earth tones dominate, but imported dyes and colored cottons were used. There are many motifs, but usually 3-4 were incorporated into each piece, and the creator of a new motif was granted unwritten copyrights. Certain motifs were used to indicate royalty, celebrate family occasions, and as talisman to protect warriors and pregnant women.

Bamako, Ghana, Mali, and Sonhai Mud Cloths

Widely known today as “mud cloth,” “bogolan” is the name used for this textile developed in the Songhai and Mali empires of the 15th and 16th century. Men wove the cloth on narrow looms, and soaked the fabric in a dye bath of leaves. When dried, the fabric is yellow, and women apply the fermented mud “slip,” which can be infused with iron to create a black pigment. A chemical reaction between the yellow cloth and the mud “stains” the fabric, so the dark color remains after the mud is washed off. The yellow is removed, so the final cloth is white with dark brown to black patterning. The fabric was considered a ritual protection and badge of status, which is why warriors wore the fabric in battle, and women after childbirth.

Yoruba Adire Cloth is from Nigeria, and is an indigo dyed cloth using various resist-dye techniques. The techniques include:

Oniko: raffia tied around pebbles or corn kernels to produce small circles

Alabere: raffia is actually sewn into the fabric before dyeing

Eleko: pattern is created by painting or printing cassava paste onto the fabric. (Cassava is a starchy root vegetable.)

Moroccan Sash was based on a traditional wedding garment worn in Moroccan Muslim and Sephardi Jewish wedding ceremonies and is known as “l’ahzem.” It served as a decorative element, as well as a corset. The design commonly included the “Khamsa” or “Hamsa” design, which is an abstracted hand.

Congo Kuba is a raffia cloth woven on a single-heddle loom, and finished by pounding with a mortar to soften the cloth. Traditional Kuba patterns are based on the interruption of expected lines, and traditionally there isn’t a repeat. The cloth was used for ceremonial skirts, tribute cloths, headdresses and basketry.

I am constantly amazed at the technical innovations of the creators, who did not have the opportunity to access the shared knowledge of techniques and constructions from other cultures. These creators were true innovators. It is amazing to see how these traditions continue to influence contemporary textiles, and it is equally important to understand the sources.

We’re honored to share and preserve these textile developments and innovations, and the women who created them. Check back soon as we revisit some of my very favorite pieces drawn from South America.

Revisiting Womens Work – South America

Bolivian Knit is another reference from the knit tradition, brought by European explorers in the mid 16th century to South America. The supply of wool from local sources came from alpaca, llama and vicuna, and the tradition evolved into intricately patterned, fine gauge small garments, like hats and purses.

Guna Mola is another reference from South America, specifically Panama and Columbia. The orgin of the pattern is from handmade fabric used in traditional garments of the Guan. The patterns developed from body painting by the women of the tribe, and these patterns were later translated onto fabric as the Guna were influenced by colonization and the Christian missionaries. The molas became politized in the early 1900’s, and became a symbol of their eventual independence from the Pamanmaian government. The process is similar to Hawaiian quilts – several layers of fabric are sewn together, and the design is created by cutting away, and finishing the edges of the fabric. This is a complex fabric, and source of great pride for the Guna women as the quality of the stitching and design are considered an indication of great skill.

Huari Tapestry originated with the Wari Civilization, which is now part of Peru. The textiles are part of their burial tradition, so many references exist today. Motifs include geometric shapes, with an occasional single random motif or color placement, possible the makers’ mark. Animals and plants important to their culture were represented, such as plants, cactus, pumas, condors and especially llamas.

Revisitng Womens Work – Central and North America

Colonial Coverlet

Hildago Otomi

Inuit Beaading

Mayan Huipil

Potawatomi Applique

Tlingit Chilkat

Revisiting Womens Work – Asia and India and Australia

Pandanus Basket

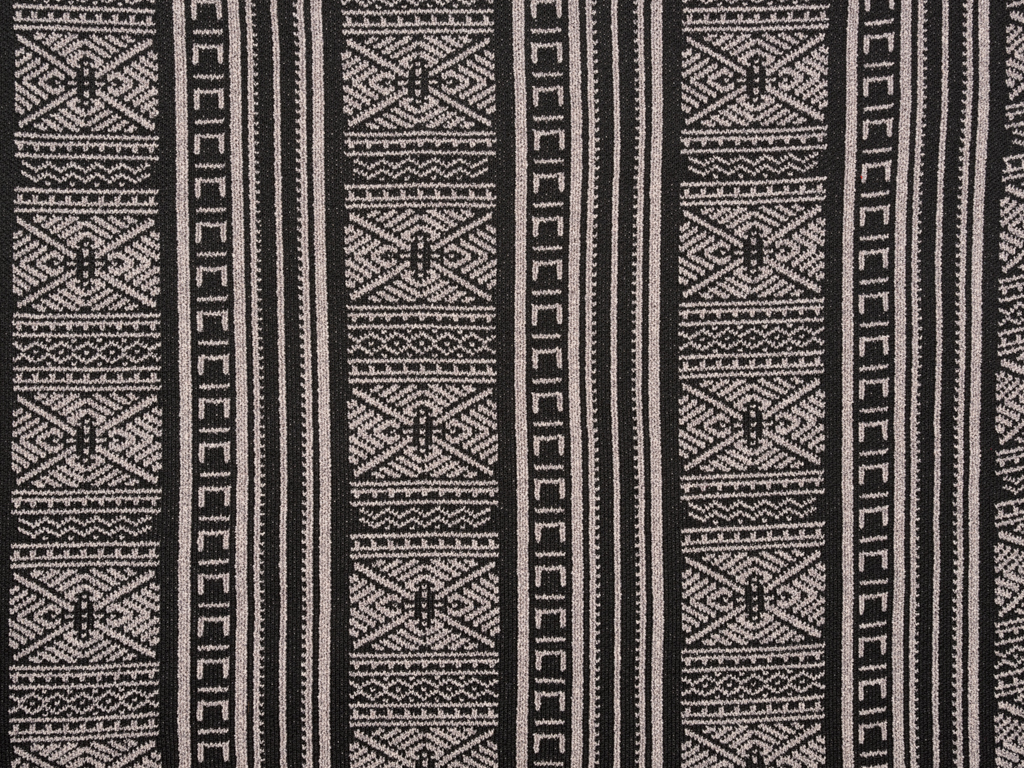

Bhutan Tigma

Chinese Embroidery

Figi Barkcloth

Samarkand Ikat

Indian Kimbkhab

Indonesian Batik

Japanese Sanshi

Laos Silk

Limbu Dhaka

Minang Sonket

Revisiting Womens Work – Europe, Russia and the Baltic Region

English Lace

Istanbul Silk

Polish Parzenica

Sarafan Embroidery

Scottich Fair Isle

Serbian Sare

Ukranian Rushnyk

Usbek Suzani