![]()

![]()

Earlier in the year, we packed our bags and took you on a whirlwind tour from Ghana to Peru, exploring some of the history of these places through the lens of women and textiles. Our “Women’s Work” collection, which earned the 2019 Hospitality Design Textile award, is a huge source of pride for our team — not just because of the national recognition, but mostly because it honors the work of the women who came before us, all over the globe. In our first “tours,” we revisited the crafts(woman)ship of Africa and the Americas, spotlighting some of the fabrics from the collection and exploring their history. Now, for our final installment in this series, we’re taking you through the Middle East, Asia, and Australia.

Earlier in the year, we packed our bags and took you on a whirlwind tour from Ghana to Peru, exploring some of the history of these places through the lens of women and textiles. Our “Women’s Work” collection, which earned the 2019 Hospitality Design Textile award, is a huge source of pride for our team — not just because of the national recognition, but mostly because it honors the work of the women who came before us, all over the globe. In our first “tours,” we revisited the crafts(woman)ship of Africa and the Americas, spotlighting some of the fabrics from the collection and exploring their history. Now, for our final installment in this series, we’re taking you through the Middle East, Asia, and Australia.

Let’s start with Pandanus Basket, which references the Aboriginal Australians and the materials they used in textiles: bark, hair, string, and grass. The fabric’s namesake, the pandanus plant, is a palm-like tree commonly used in traditional fiber crafts — a classic example of craftspeople making use of the abundant natural resources available to them. Before weaving pandanus into intricate baskets or mats, artisans would harvest young leaves, slice them into fine strips, then dye the strips with roots and leaves.

Hailing from the tiny nation of Bhutan in the Eastern Himalayas, the Bhutan Tigma is a ceremonial woven textile distinguishable for the abundance of colors, sophistication and variation of patterns, as well as the intricate dyeing and weaving techniques. The textile is made in narrow strips and sewn together, with tie-dye techniques creating the patterns. Farmers would weave when they had free time from agricultural work, but the royal weavers were considered the professionals. Their work surpassed the utilitarian realm of clothing; it was seen as a form of wealth and status, and used as commodity for trade and taxation. Bhutan textiles use a variety of weave construction such as plain weave, warp pattern weave, and weft pattern weave and are also categorized by the colors used. (Red is most commonly worn by women.)

Chinese Embroidery hearkens back to the long-standing textile tradition in China, going back to the 5th to 6th century BC. Although there are many motifs from this culture, we focused on clouds, which are considered lucky. The iconography is heavily featured in Chinese patterns and symbolism with connections to everything from rain for crops to the heavens to the union of yin and yang (plus dragons and bats). The cloud pattern is attributed to the Ming and Qing dynasties, and was adapted into weaving during the Yuan dynasty.

In the Fiji tradition of barkcloth, which dates back to the Neolithic period, artisans transformed tree bark into ornate textile goods, represented here in Fiji Barkcloth. Trees were stripped and their bark was beaten into sheets, then used to make everything from art to clothing. One particular form of this is tapa cloth, which is specific to the islands of the Pacific Ocean. Craftspeople decorated the cloth by rubbing, stamping, stenciling, smoking, and/or dyeing, traditionally in hues of rust brown and black. These traditional cloths are also prized for their decorative value — a Tongan family is considered poor if they do not have any tapa stock at home to donate at life events. Gifts of tapa cloth from royalty are considered more valuable.

Indonesian Batik pays homage to batik, the technique of wax-resist dyeing by either drawing dots and lines of the resist with a spouted tool called a canting or by printing the resist with a copper stamp called a cap. The traditional of batik can be found in various countries, including 4th century BC Egypt, the Chinese’s Tang Dynasty from 618 to 907 AD, and the Japanese Nara period from 645-749 AD, but the Indonesian island of Java is credited as the origin of the technique (and, in 2009, was recognized for that cultural contribution by UNESCO). Materials like cotton, beeswax, and many different vegetables (for dye) abound on Java, and artisans made use of all of it in their batik textiles, preparing and washing the cloth before drawing patterns on the cloth with the resist material, which was later removed by boiling or scraping the fabric. Each pattern carried its own significance: infants are carried in batik slings decorated with symbols designed to bring the child good luck, and batiks are prominent in the Japanese “tedak siten” ceremony when a child touches the earth for the first time. Some designs are reserved for royalty and banned from being worn by commoners (making it easy to discern someone’s class status by the pattern they wear).

Upcycling might be a relatively recent term, but artisans have made use of leftovers and discarded fabrics for generations. An early version of this textile recycling is the Japanese Sanshi: in this practice, cloth was woven using the leftover threads of previously woven fabrics. Broken warp threads and leftover bobbins are tied together to make a continuous length that can be woven again into a new fabric.

Laos Silk tells a story of acculturation, in textile form. Silk, along with silk weaving, dying, and cultivation techniques, was introduced to the region when Tai-Laos people migrated from Southern China. When they encountered the indigenous Mon-Khmer people, who used back-strap looms to weave other materials like raw cotton and hemp, the cultural contact birthed a distinctive kind of silk. Now, the weaving of traditional designs is, well, woven into the culture, with most Laotian women learning the technique as young girls at their mothers’ looms.

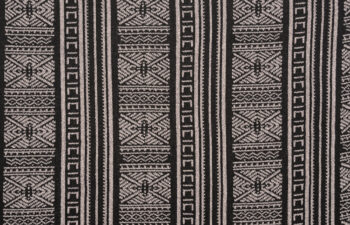

Limbu Dhaka is from the Nepalese weaving tradition, which dates back to 450 AD. This cotton woven fabric is characterized by colorful geometric designs. (Modern-day versions are made from bamboo, cotton, and hemp.) Cut off from much of the rest of the world for many generations, Nepal has cultivated a strong tradition of handmade textiles, including rugs, bags, blankets and clothing.

Minang people are from the highlands of West Sumatra, Indonesia (which might sound familiar to caffeine addicts — the region is known not just for its intricate textiles, but also for its coffee). The Minang Songket is a sophisticated brocade, hand-woven with silk or cotton and patterned with gold or silver threads. In a technique called supplementary weft, Minang artisans inserted metallic threads between silk or cotton threads, yielding an overall shimmering effect. The resulting garments were typically worn for ceremonial occasions, religious festivals, and social functions. Ancient artisans may have even used real gold threads by running cotton threads along heated liquid gold to coat the thread. Songket weaving is a complicated process, and as such, it’s believed to cultivate virtues like diligence, carefulness, and patience.

No one is exactly sure how old the technique of ikat is (some say 18th century, others say 10th or 11th century), but its epicenter lies

Though the tradition was suppressed under Soviet rule, the Uzbekistan city of Margilan has produced some of the finest silks of central Asia for generations. Samarkand Ikat celebrates this ancient tradition, which is characterized by large, bold designs: pomegranates and tulips, scorpions and spiders, birds and ram’s horns, all rendered in bright primary colors. Ikat textiles are used for robes, linings, wall hangings, and coverlets, and are considered a luxury reserved for special occasions and gifts. Ikat is one of the oldest forms of textile decoration and is prevalent in many regions around the world.

We feel honored to re-introduce and reinterpret these traditional patterns as the rich cultural artifacts that they are — and as the legacies of the craftswomen around the globe who preceded us. We hope “Women’s Work” resonates with you as it does with us.